Since the early 2000’s, financial institutions have recognised the importance of organisational environment on managing risk. Regarding the 2017 Financial Services, Royal Commission Kenneth Hayes wrote “Culture, governance and remuneration. Each of those words can provoke a torrent of clichés. Each can provoke serious debate about definition. But there is no other vocabulary available to discuss issues that lie at the centre of what has happened in Australia’s financial services entities and with which this Report must deal.” The term “risk culture” has increasingly been used to describe how financial institutions manage the human element of risk. However, this term is technically inaccurate and can result in organisations investing time and effort into less effective interventions. In the below article, I aim to explain the differences between risk culture and the technically correct term risk climate, and how this understanding is vital for any organisation hoping to effectively manage risk.

Difference between culture and climate

Before we can manage the people components of risk we must first obtain a solid conceptual and practical foundation of the concepts involved. After all, how you think about risk culture/climate naturally determines how you will use it. I strongly encourage becoming familiar with the differences explained below.

Can you think about how you might tailor your approach if you were managing risk culture vs risk climate? What effect might that have on our outcomes?

Risk Climate not Risk Culture

It may come as a surprise to you (it was to me when I first found this out) that the term risk culture is actually a colloquialism. Risk culture has its origins in risk climate research and this distinction has vital implications on the work of risk culture work.

People familiar with culture literature, hearing the term “risk culture” may be tempted to lift and shift the models they are familiar with to address the challenges, the models would be based on the logic that underlying values and beliefs are what is driving the change and that larger-scale interventions are needed to shift the needle on risk behaviours. This can result in interventions that are less effective. A classic example of applying culture thinking to a climate problem is that of “tone from the top” which has become a popular refrain in the risk culture space. It suggests that top senior leader communications impact risk behaviours of team members. Whilst this may be true, research shows that the behaviour of team managers may be more impactful on individual behaviour. Professor Elizabeth Sheedy a prominent researcher in this space co-authored a 2017 paper on the topic, writing:

Contrary to the “tone at the top” hypothesis, there were significant differences in risk culture factor scores between different business units even within the same bank. Rather, the data support the proposition that culture exists at the local level as staff interact with one another and look to local management for guidance. The implication is that risk culture should be measured and managed at a sub‐firm level – whether that is best done in business units as in the current study, or at lower team units, is for further research to ascertain. It is further important to understand that managers throughout the organization must come under scrutiny, not just those at the top.“

Note the term risk culture is used in this paper because that is what is used in the financial sector…

In fact, psychologists generally measure “climate” rather than “culture” due to the difficulty that staff typically have in articulating the underlying assumptions and values of the group. In contrast to culture, climate relates to the more easily observed practices of the group and the meaning that is associated with those practices. As practices arguably flow from values and beliefs, they can be seen as a proxy for values. We note that the financial sector’s practitioner and industry literature exclusively uses the term “risk culture” even when referring to surveys and concepts developed in the climate tradition. We have adopted the same convention.“

Once we understand the fundamental differences between these concepts, the terminology we use doesn’t matter as much. What matters is that now we can begin to apply frameworks that are much better suited to the outcomes we are seeking.

Use a risk culture/climate model that’s fit for purpose

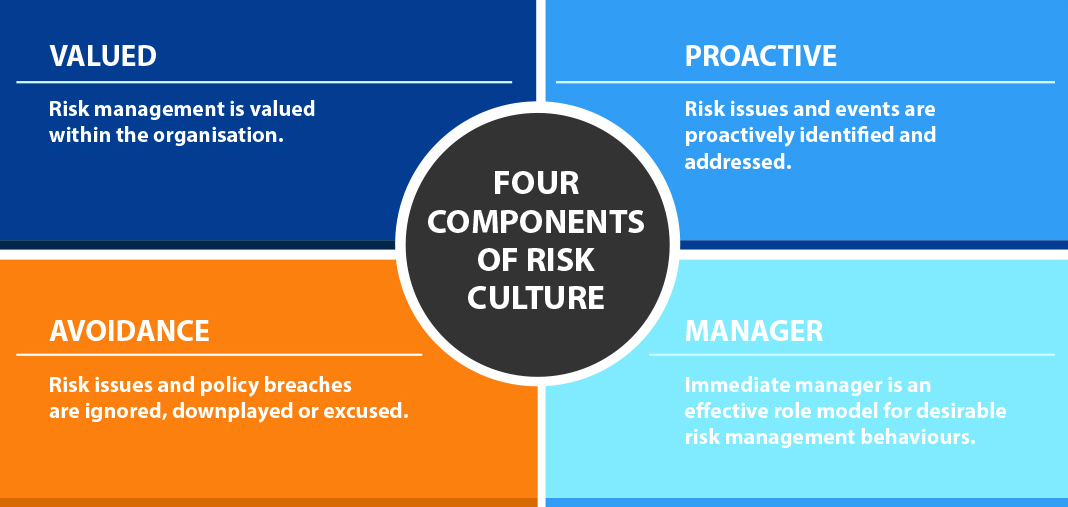

Sheedy and the team at Macquarie University have developed a psychometrically sound measure of risk culture which has been shown to predict poor risk and control outcomes, such as misconduct and non-compliance. It consists of four elements:

Is a Proactive approach taken to risk management where events are identified early via constructive discussions rather than blaming/shaming?

Does the immediate Manager role model the correct behaviours such as reporting and resolving risk issues and complying with policies?

Is risk management Valued by team members or are policies tick the boxes activities staff wish they didn’t have to do.

To teams demonstrate Avoidance of risk management behaviours as they conflict with short term profits or cost reduction. For example, can top performers get away with non-compliance. This factor was found to be the most important element for predicting poor risk outcomes and Sheedy suggests it be included in all risk culture models.

For more detail on the model and its applications see the paper “Auditing Risk Culture: A practical guide“.

In a recent interview with the AFR Sheedy stated “The whole risk culture space has become a very big source of fees for consultants and I don’t think all of them have done a good job in coming up with a valuable and robust model,” I agree with this sentiment…

So next time you are asked to improve the risk culture of an organisation ask yourself:

What is the problem we are trying to solve?

What is the simplest and easiest way to immediately solve this problem?

What fit for purpose risk climate lens could I apply to understand the people elements of this problem?

References:

Arzadon, Preeze, & Sheedy, (2021) Auditing Risk Culture: A practical guide. The Institute of Internal Auditors Australia.

Ehrhart, M. G., Schneider, B., & Macey, W. H. (2013). Organizational climate and culture: An introduction to theory, research, and practice. Routledge.

Macquarie University – Research Findings, Business and Economics, Macquarie University. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.mq.edu.au/research/research-centres-groups-and-facilities/prosperous-economies/centres/centre-for-risk-analytics/our-projects/projects/elements-of-risk-governance-and-culture-cifr-e039-,-business-and-economics,-macq/research-findings,-business-and-economics,-macquarie-university

Sheedy, E., Griffin, B., & Barbour, J. (2015). A Framework and Measure for Examining Risk Climate in Financial Institutions. Journal Of Business And Psychology, 32(1), 101-116. doi: 10.1007/s10869-015-9424-7

Sheedy, E., & Griffin, B. (2017). Risk governance, structures, culture, and behavior: A view from the inside. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 26(1), 4-22. doi: 10.1111/corg.12200

Sheedy, E. (2020). Risk Culture v Risk Climate: What’s the difference? LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/risk-culture-v-climate-whats-difference-elizabeth-sheedy/