This article is a condensed summary of the first two sections in James Nelson’s textbook, Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. The sections covered are What is Religion and What is Spirituality? I hope this simplified view will help individuals quickly form a baseline understanding of the human experience and practice of religion and encourage them to explore the topic further.

Below is a mindmap of the topics that are covered. Most of the content below is taken directly from Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality with paraphrasing and comments by myself. I conclude with my observations from an Organisational Psychology perspective on the introduction of religious practices into the workplace.

What is Religion?

Religion has to do not only with the transcendent as it is “out there” but also as it is immanent in our bodily life, daily experiences, and practices.

Transcendence

Our relationship with the Devine or transcendent – that which is greater than us “the source and goal of all human life and value”.

Immanence

Activities and a way of life: “the fashioning of distinctive emotions; of distinctive habits, practices, or virtues; of distinctive purposes, desires, passions, and commitments; and of distinctive beliefs and ways of thinking,” along with “a distinctive way of living together” and a language for discussing “what they are doing and why”.

Some religious traditions like Islam are thought to emphasize transcendence, while Eastern religions tend to emphasize immanence. Christianity stresses both: the transcendent God is also the God who can be found within and around us, discernable in both a dramatic religious experience and in the simple, quiet love of a child for his or her parent.

Are religions more about the transcendence of immanence? While some religions may emphasize one over the other, all the great religious traditions encompass both

Transcendence

Weak Transcendence: When something takes us beyond our current state of mind or way of being, thinking, and feeling. Such as listening to a moving piece of music, looking at the stars or mountain range, or watching a movie. These are considered weak as although they are “beyond us”, it is something that can be achieved or comprehended, often without a fundamental change in our way of life or outlook.

Strong Transcendence: Sometimes, however, we encounter more radical forms of strong transcendence that defy comprehension, understanding, and control. This happens when we find that life cannot be put into a box or reduced to a set of propositions and rules despite our best efforts. In the words of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (1969), we find that our world is not just a settled, controllable “totality” of a clearly understood system but is an “infinity” that sometimes goes beyond our human control and understanding.

|

Theism:

For many people around the world, this transcendence is not just an abstraction, but it has a personal quality. The something that is beyond relates to us in love, and we in return offer it our love.

|

Nontheistic:

Nontheistic religions may acknowledge strong transcendence but deny its personal quality. This is a traditional stance in Buddhism.

The Numinous

In his book, The Problem of Pain, C.S. Lewis describes the concept of “The Numinous” in a way that I believe captures at least one aspect of the transcendent experience.

Suppose you were told that there was a tiger in the next room: you would know that you were in danger and would probably feel fear. But if you were told ‘There is a ghost in the next room,’ and believed it, you would feel, indeed, what is often called fear, but of a different kind. It would not be based on the knowledge of danger, for no one is primarily afraid of what a ghost may do to him, but of the mere fact that it is a ghost. It is ‘uncanny’ rather than dangerous, and the special kind of fear it excites may be called Dread. With the Uncanny one has reached the fringes of the Numinous. Now suppose that you were told simply ‘There is a mighty spirit in the room’ and believed it. Your feelings would then be even less like the mere fear of danger: but the disturbance would be profound. You would feel wonder and a certain shrinking–described as awe.

Implications on Science: Strong Transcendence shows the potential limitations of science. Scientists can prefer tidy models which are measurable and stick within the confines of rationality. However, by its very nature, transcendence defies these. For a believer the afterlife is entirely real; some scientists would find this difficult to accept because it is not directly observable. We must avoid the tendency to assume that all religion can be explained by Psychology when it obviously excludes critical aspects of the phenomena.

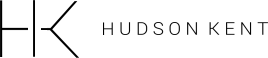

Immanence

Values/Worldview: Many experts prefer to see religion as a particular type of human activity. For example sociologists, Charles Glock and Rodney Stark see religion in relation to our values. People develop value orientations “over-arching and sacred systems of symbols, beliefs, values, and

practices concerning ultimate meaning which men shape to interpret their world”. By this definition, Marxism and other secular systems of thought are akin to religion as they provide value orientations. For more information on the values system behind Marxism, you can read my chapter summary of The Communist Manifesto.

Although Marxists “conceive of themselves, on the whole, as antireligious, they can be thought of as offering a worldview – a basic set of assumptions and way of thinking about self, the world and our place in it. The Marxist utopia could even be viewed as an appeal to transcendence. Secular worldviews often appear to fill some of the same functions as a religion by providing an ideology, or system of thought, that attempts to explain everything from a single premise.

Activities: Many also see religion as a social phenomenon embedded in our day-to-day actions. Ninian Smart (1998) identifies religion as a human activity with some or all of the following dimensions: (1) practical and ritual, including prayer, worship, and meditation; (2) experiential and

emotional; (3) narrative or mythic; (4) doctrinal and philosophical; (5) ethical and legal; (6) social and institutional; and (7) material, including buildings and other artifacts.

Culture: Some scholars prefer to look at religion as part of culture, the complex whole of “capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society, especially the “webs of significance” available in society that help us in the search for meaning. There are two ways of approaching cultural phenomena. The etic Model and the emic Model.

|

Etic Model:

In the etic model, cultural forms are seen as universal phenomena with similar characteristics across all cultural settings. In the case of religion, an etic view assumes that all religions share certain attributes like having a view of transcendence, and that they can be broken down and analyzed according to a universal set of categories, as when we compare Christianity and Buddhism on their “devotional practices.”

|

Emic Model:

In the emic model, each cultural form is thought to be unique and occurs within a given physical, social, and historical context. An emic view of religion would argue that two different religions

are not just alternate varieties of the same thing; rather they are unique systems and each must be understood and evaluated on its own merit.

Both of these approaches can be found in the contemporary psychology and religion literature, with scientists tending to use etic models and theologians or religious studies scholars arguing more from an emic stance.

Definitions of religion that view it as a human activity often have two implications. First, if religion is defined as a worldview, it is possible to speak of everyone as being religious since everyone has a worldview. Second is that this can lead to the functional analysis of a religion (looking at it in terms of what it does), rather than a substantive analysis (specific content and beliefs). Functional analysis could be reductionistic as it may imply that a religion is only about its functions and not about its substance, such as views on transcendent reality.

What is Spirituality?

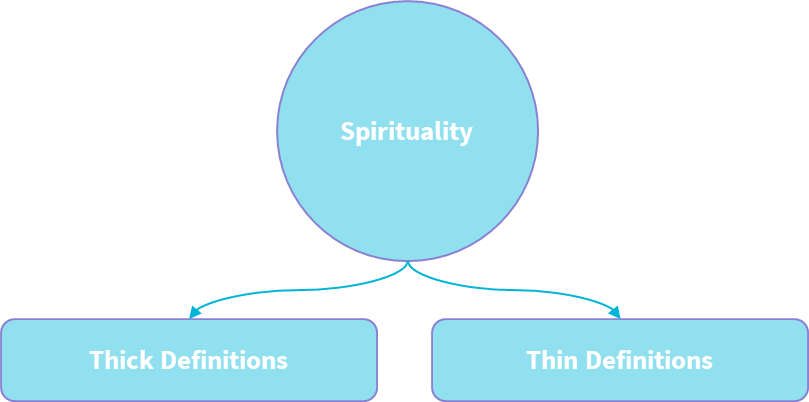

The term Spiritual has evolved over time. In its original English Spiritual “spiritual” was a term used to contrast church life with “worldly” or materialistic ways of being. Today the term is often used to denote the experiential and personal side of our relationship to the transcendent or sacred.

Those who use the term in this way typically contrast it with religion, which they define narrowly as the organizational structures, practices, and beliefs of a religious group. Theologians and religious practitioners, on the other hand, tend to prefer definitions that draw less of a strict division between religion and spirituality. In their eyes, spirituality is the living reality of religion as experienced by an adherent of the tradition.

Thick vs Thin conceptions of spirituality: Religious conceptions of spirituality generally involve thick definitions that are rich in allusions to specific beliefs and practices, as opposed to thin or generic “one size fits all” definitions that focus more on natural experiences, personal values, or

connectedness. For example:

|

Thin definitions

A thin definition might be “the organization (centering) of individual and collective life around dynamic patterns of meanings, values, and relationships that are trusted to make life worthwhile (or, at least, livable) and death meaningful.”

|

Thick definitions

His thick definition of Christian spirituality is more specific: “the organization

(centering) of individual and collective life around loving relationships with

God, neighbor, self, and all of creation—responding to the love of God revealed

in Jesus Christ and at work through the Holy Spirit.”

Given that religion and spirituality are complex concepts that have different meanings for different groups. Any definition that focuses on only one aspect of spirituality or religion should be avoided.

Concluding remarks from an Organisational Psychology perspective

Organisations are more and more willing to adopt religious practices into their operations. Mindfulness seminars, performance coaches and wellbeing counsellors are accessible; even a cohesive set of cultural behaviours and values through which to view the world could all be considered to be reflections of what was originally a strictly religious practice. Fred Kofman former Vice President of Leadership and Development at Google referred to himself as the “Chief Spiritual Officer”. As organisations take on more and more responsibility for individuals’ wellbeing, they are making investments into human capital that would have been unprecedented from a business 30 years ago. This means that for some, work is quickly replacing the social and emotional functions previously served by religious institutions.